A character in Oscar Wilde’s play Lady Windermere’s Fan famously defines a cynic as one who “knows the price of everything, and the value of nothing.” When it comes to shaping public opinion concerning the carbon economy, it’s fair to say climate alarmism—and the bleak lens through which it views the future—in prevailing.

All of us are now keenly aware of the price we pay as a society for our so-called addiction to fossil fuels. We know that coal-fired electric plants spew harmful particulate matter and are responsible for greenhouse gas emissions that can alter Earth’s climate.

We also know that our ubiquitous internal-combustion-engines consume 80 gallons of petroleum each year for every person on the planet. And we’re now aware that natural gas, though less of an offender, is also guilty, especially as leaky pipelines allow climate-killing methane into the atmosphere.

The implication of this parade of horribles is that our thirst for energy is the overriding sin of our day. But this is a distorted view—one that misses the value of human progress and the catalyzing role that low-cost and readily available energy plays in that process.

It’s fashionable to point to a future in which fossil fuels are no longer so central to our lives. But on which activities, goods and services will we compromise to get there?

For example, the iron and steel needed to build everything from bridges to wind turbines represents about 7% of emissions. Road transport—including daily commutes, the delivery of agricultural goods from the field to stores and restaurants, and road trips to see loved ones—is about 12 % of emissions. The energy to power our homes is another 11%. Chemicals and cement, essential building blocks in much of modern industry and construction, are 5%. The list goes on.

If we are to balance the needs of all mankind, we must acknowledge the innovation and prosperity that go hand-in-hand with convenient and reliable energy. A little over a hundred years ago, only two-percent of households in the developed world were equipped with electricity. Today, virtually all have access to this life-changing utility.

Affordable energy has helped eliminate living conditions that contribute to tuberculosis, pneumonia and dysentery—diseases once responsible for almost half of all deaths in Western society. The vast majority of Americans living beneath the poverty line today possess and benefit from such energy-driven amenities as cell phones, televisions, refrigerators, electric or gas stoves, and microwaves.

Globally, the trends are similar. According to the World Bank, the average life expectancy at birth worldwide in 1960 was 52.6 years and infant mortality was 22.5%. In the years since, life expectancy has risen to 72.5 years as infant mortality has declined to 2.5%.

Fifty years ago, half of humanity lived in extreme poverty; today, the figure is less than 9%. Meanwhile, the share of the global population deemed to be undernourished has fallen from 28% to roughly 10%.

The environment is also benefiting as we’ve gained the means to take better care of the planet. Oil spills of 1,000 tonnes or more have fallen from a peak of 636 in 1979 to fewer than 10 a year since 2010. One-seventh of Earth’s land surface is now protected as national parks and reserves—a five-fold increase since 1960.

In 1986, 193 countries allowed the sale of leaded gasoline. Only three do so today. The use of ozone-depleting substances has fallen from 1.6 million tonnes per year in 1970 to virtually zero. Smoke, as measured by S02 particles emitted per person, has fallen by two-thirds over the same period. And carbon emissions from human activities is growing at half the worst-case rate projected in 2013 by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Sadly, there’s little attention given to these and other achievements in the media. Nor do we hear much when dire predictions are proven wrong. For instance, a 2013 article in USA Today pushed the then-current worst-case forecast that the North Pole would be ice-free by the summer of 2020. In reality, the ice-cap covered 1.44 million square miles at its lowest in 2020—27% below the 2013 low-point. The worst-case didn’t materialize, despite the Arctic warming at twice the rate of the rest of the planet. You’d never know the from the headlines.

The media aren’t the only ones peddling misinformation in an effort to trigger the public’s inclination to act. Climate activists regularly traffic in their own bald exaggerations. In his 2018 book, Factfulness, Hans Rosling recounts environmental celebrity Al Gore’s stark admonitions to focus exclusively on worst-case climate forecasts without showing comparable data for the most-likely and best-case scenarios. “We need to create fear,” Gore insisted.

None of this is to say that a goal of lower carbon emissions isn’t a good thing. But human progress advances along multiple vectors. It’s easy to demand that we replace our carbon-based system with cleaner alternatives, but solving complex problems through substitution is never simple or straightforward. Replacements often have their own unforeseen deficiencies—some of which can pose as much (or more) risk as the status quo.

Take, for example, the full-circle evolution of the American grocery bag. For decades, virtually all grocery bags were made of paper. But in the late 1970s, environmentalists began to point out that the use of paper bags helped kill large numbers of trees. The public agreed that it was time for a change.

To reduce our dependence on paper and save our forests, we turned to what was then seen as the product of the future—plastic. A thousand times stronger than paper and only a fraction of the cost, plastic bags were considered a smart way to help solve the problem of deforestation. Until some ugly realities began to surface.

Plastic bags, it turns out, are so cheap and easily disposable that hundreds of billions of them now fill our landfills, pollute our landscapes and float in our oceans. The cure was as harmful as the illness.

In response came the movement to replace plastic bags with reusable ones. These multi-use bags, the theory went, can be used repeatedly and with little impact to the environment. Unfortunately, advocates overlooked certain health risks. Studies find that the bags can become hosts for all types of harmful bacteria, including E. coli and other coliform. Washing after use is no safeguard since others’ dirty bags can contaminate shopping carts, checkout counters and food items.

Even more vexing is the large environmental impact of reusable totes manufactured with natural materials. A Danish study concluded that a single organic cotton bag has environmental effects so large that it must be used at least 20,000 times before it is a better choice for the environment than a typical plastic bag.

Frustrated, many retailers have given up chasing the ghost. Whole Foods Markets, which once saw the use of paper bags as unconscionable, now utilizes them exclusively. Others offer the choice of “paper or plastic.” Despite the health risks, as much as a third of younger Americans use reusable bags. The solution, it turns out, wasn’t to eliminate paper bags. It was to reduce their use via consumer choice.

None of this should come as a surprise. As John D. Sterman, Professor of Management and director of the System Dynamics Group at the MIT Sloan School of Management notes, “There are no side effects—only effects.” As with the movement to save the planet from shoppers, unintended consequences inevitably crop up regardless of the purity of motives. It’s an immutable truth, with examples beyond just shopping bags.

Fuel additives used to decrease carbon monoxide in the air have leaked cancer-causing agents into drinking-water supplies, as have measures designed to disinfect water supplies themselves. And U.S. government regulations to reduce logging actually led to more trees being felled and species threatened in other parts of the world, as countries less committed to responsible conservation filled the gap. The ban on DDT has almost certainly led to millions more deaths worldwide, as malaria has increased dramatically in countries that no longer use the insecticide.

To be sure, the carbon economy has had its own negative impacts. Over the last century, the growing number of uses for, and dependence on, fossil fuels has touched virtually every part of the natural world. What has followed, however, is a learning curve expressing our ability to mitigate many of these impacts as they’ve become apparent over time.

Contrast this to where we are with the green economy. Unpopular as it is to point out, many of the alternative forms of energy now being touted as preferable to fossil fuels will have their own environmental, economic and social drawbacks. Some will prove highly problematic.

The relatively small number of adverse effects so far attributed to solar, wind and other renewable forms of energy is a function of how little we know. The installed base of projects is too small, and it’s too early in the process to understand how externalities will manifest (and accumulate) over time. The most obvious risk is reduced energy reliability coupled with higher costs, owing to the intermittent nature of many forms of renewable energy.

There are other risks, too. Case in point, we are yet to understand the long-term health impacts of packing electric vehicles and charging stations into urban areas. As the energy density of batteries increases and charge-times fall, the potential effects on human health grow.

In addition, battery stacks in battery electric vehicles (BEVs) must be replaced every few years as they weaken. The hope is that responsible and cost effective recycling and disposal will save the day. But given that the cost of extracting old lithium is five times higher than the cost of mining the metal, we shouldn’t hold our breath.

Likewise, wind farms may lower the quality of human and animal life through noise and visual impacts. Many environmentalists are concerned about their impact on migratory birds and raptors, including protected species. The challenge of disposing of discarded turbines will also prove daunting, with the EPA calling each new turbine a “towering promise of future wreckage.”

Solar farms, which often occupy vast tracts of land, can degrade and displace the habitats of native plant and animal life. And waste from older industrial and residential solar installations is already straining recycling and disposal capacity, with some materials ending up in municipal landfills. Falling costs for new panels only further reduce economic incentives to recycle disused panels.

It’s unclear how long it will take to identify and address problems arising from today’s move toward alternative forms of energy. But when we do, the best of the carbon economy—driven by its continual efficiency and conservation gains—will likely appear increasingly attractive by comparison.

There are other reasons to expect fossil fuels to remain in demand. With four-fifths of the world’s population now living in developing countries, continued human progress will require inexpensive and readily available energy. Transport will need to be expanded, roads and hospitals built, schools and businesses established, and commerce and trade opened up.

It is impractical to assume that we can eliminate global emissions while providing the resources to improve the lives of these billions of people. Moreover, it’s not the place of richer nations to dictate energy policy to poorer ones.

Nor is it realistic to believe the U.S.—currently responsible for only 15% of global greenhouse emissions—can sacrifice its way to mending Earth’s climate. Yet there’s no shortage of feel-good narratives suggesting just this. Some have even compared the proposed Green New Deal (GND) to the Apollo space program of the 1960s. It’s a weak analogy.

It cost about $160 billion in 2021 dollars to put a man on the moon in 1969. The GND’s cost for just the U.S. is estimated at more than 500 times that amount. As Bill Gates noted, the tab for similar efforts in more than 190 countries globally would be “beyond astronomical.”

Moreover, America’s ambitions in space never risked bankrupting mankind or threatened the living standards of future generations. If our efforts had failed, we would have lost the lives of a few brave astronauts and some government expenditure. But ordinary people’s lives would not have been turned upside down by habitually catastrophizing media, politicians and bureaucrats pursuing some distant goal arbitrarily and subjectively formulated by global elites.

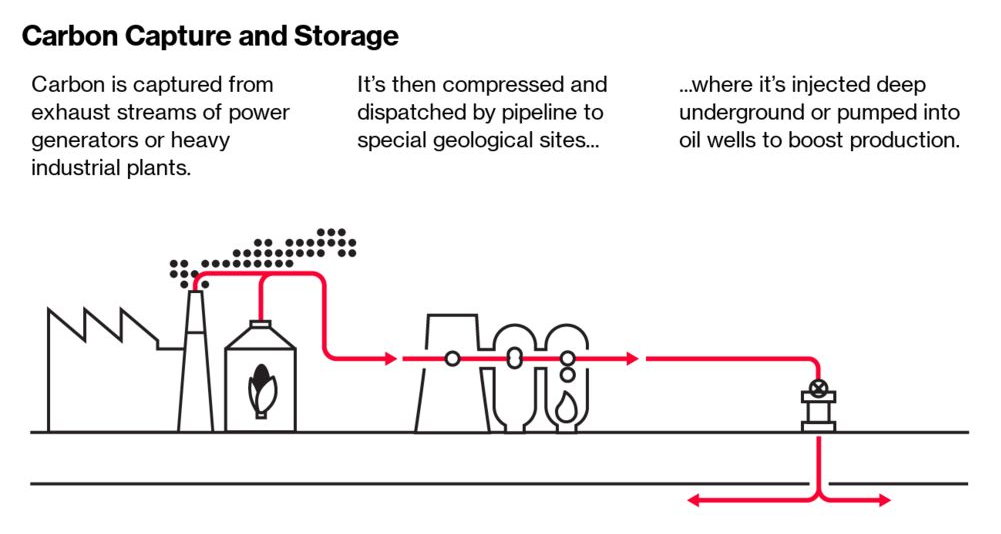

As the limits and disadvantages of a hoped for wholesale shift away from fossil fuels reveal themselves, we should not be surprised to see interest in carbon capture and storage (CCS) intensify. After all, if we are serious about reducing the amount of CO2 that lingers in the atmosphere, it cannot just be about what we put into the environment—it must also be about what we take out.

It’s a given that the planting and preservation of long-lived trees and plants will increase. But so will investment in direct capture of CO2 from power plants, factories, and even the open air. If we’re right, it’s not hard to imagine fossil fuels—especially oil and gas—playing similar roles decades from now as they do today while renewables power CSS facilities that scrub CO2 from the atmosphere.

But CCS is an expensive option and likely won’t move the needle much on global emissions. That means we’ll need more research to develop better and less-expensive solutions. Owners of fossil fuel reserves are well positioned to pay for the research and development. The incentives are certainly there. At $50 per barrel and $3 per MMBtu, annual global oil and gas production is worth about $2 trillion. If enough CO2 could be removed from the atmosphere each year to preserve 10% of that revenue, the oil and gas industry alone could justify spending up to $200 billion a year—or $4 trillion over 20 years—on better technology .

Other segments of the economy dependent on fossil fuels—such as aviation, metals, cement, plastics, and shipping—also have incentive to support the development of improved technology. A viable process would help them delay or avoid massive investments in plants and equipment and still meet emissions targets. The same is true at the governmental level, where reduced spending on new infrastructure for an all-electric world would save untold billions.

The current bias against fossil fuels distorts discussions in another important way. As we in advanced nations observe flattening demand for carbon-based energy in our own lives, we assume it will be the same in other parts of the world. In reality, both population growth and the pursuit of better living conditions in lesser-developed countries suggests global demand for fossil fuels will continue for decades. In fact, if we are serious about alleviating global inequality, it must.

The geopolitical stakes are also enormous. Indeed, it would be difficult to devise a more effective means of transferring wealth and influence from west to east than a precipitous flight to BEVs. China currently produces three-quarters of the lithium-ion batteries used in electric vehicles, and its capacity is expected to triple by 2025. It dominates the production of natural graphite and rare earths, and controls a large proportion of cobalt extracted in Africa. This all sums to a level of control far greater than OPEC ever held over oil markets.

Despite these realities, activists will continue to try to rattle us. The playbook: induce action by insisting that low-probability and distant risks are actually certain and immediate ones. We shouldn’t fall for it. Ill-conceived moonshots driven by anti-carbon reductionism will only lead to more rash decisions and unpredictable outcomes.

We risked relatively little to fly to the moon; we risk everything if we leave our economy and society to those bent on enacting laws and regulations that compromise both quality of life and individual freedoms, even as we spend money we don’t have on vague initiatives that most Americans don’t support when presented with the costs.

What America and the world need now are sober analysis, prudent decision-making, gradual action and careful monitoring. The goal should be realistic options and sound solutions that enable all people to live the lives they aspire to, including those defined by the lifestyles and opportunities of the developed world.

For now this means more baseload nuclear—and, as able, geothermal—power in lieu of coal, solar and wind. We also need more load-following natural gas plants to handle daily and seasonal variability. EVs should remain optional rather be made mandatory so as not to overload our grids or force EVs on those for whom they’re bad fits. We should focus hard on reducing fugitive methane emissions across industries. Most of all, we need to invest intensely in R&D to develop by 2050 technologies much more effective than current low-carbon solutions.

For their part, climate activists should consider proposing a national referendum on a modest economy-wide carbon tax—including the possibility of border adjustments with certain countries—with some portion of the proceeds guaranteed to go to energy technology R&D and the rest back to the people in the form of a dividend. Any carbon tax should replace or cap most other federal energy subsidies, mandates and taxes, and be required to be (re)approved by voters (not politicians) every few years.

These steps won’t get America or any other country to net zero, but they will bend the emissions curve enough to buy us time to make better decisions—based on better info and better tech—post 2050. More importantly, it’ll reduce the chance we and other nations that follow suit bankrupt ourselves throwing endless subsidies at non-solutions.

This post was originally published on June 2, 2015 under the title, ‘In Defense of the Carbon Economy” and has been revised, expanded and republished several times since. On June 3, 2025, it was republished under the title, “Seeing the World Through the Lens of Global Climate Alarmism.” It was last updated on June 3, 2025.

Well done. I enjoyed your message!

Thanks, Tim. Very glad you found it to be of interest.

Doug

Doug:

A good short Essay is done by Kathleen Hartnett White titled “Fossil Fuels: The Moral Case” is one of the best summaries on fossil fuels I have read. Ms. White is well qualified to write this essay having served as Chair of the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. I retired from Shell as a Senior Staff Environmental Engineer after working in the oil and gas industry for forty years in just about every position including digging ditches. I know this industry well working onshore, coastal, and offshore. Your Article is right on. Thanks for simply telling the truth. God loves it as He stated “I am the Truth”. God bless you.

Bill Freeman

Kingwood, Texas

Hi Bill –

Thanks so much for your comment. I was not aware of Ms. Hartnett’s essay, but I will certainly find it and read it.

Doug

Today, I received a phone call and the following note by email from Warfield “Skip” Hobbs regarding this post:

Dear Doug;

As a geologist, I am very concerned about global warming and its likely impact on the human population. When there was not a single question about energy or climate in the first Republican presidential candidate debate, I was moved to write the attached essay. I am now distributing it to policy makers, candidates, Republicans and Democrats alike, and the media. My objective is to get discussion of energy and climate into the 2016 election cycle.

Skip Hobbs

In appreciation for Skip’s taking the time to reach out to me, and in the spirit of furthering constructive discourse on the issue of climate change and what we should do (and should not) do about it, I have provided a link to Mr. Hobbs report in PDF below:

Link to Hobbs report: http://energypointresearch.com/oilfield-insights/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Republicans-Climate-Change.pdf

The sad situation about Global Warming is “it is not provable”. I find that the use of 99 models to project situations 100 years in the future without one model being correct is very telling. Ask Neal Frank, retired National Weather Bureau Director, for one who will tell you about meteorological models. I have used models too, and oh those assumptions. Trash in, trash out. But most importantly, more faith than believing in the existence of God is required. For your information about the evidence of God, much is available if you simply look. Global warming is not so easy. I have looked at this so called evidence as lacking and with very much politics involved. I started in about 1992. It is strictly a hypothesis, and truly an imaginary one. The problem is the gullibility by many who are usually environmental idealist, and without much thought about “How will we then live” as we do not allow Third World Countries to develop as we did. How selfish. It will only be the elite who will live well. Hmmmmmm

Bill Freeman

Bill;

Cheap and abundant fossil fuels made America great and improved the standard of living as cited in Doug Sheridan’s essay. However, now the business model has to change to reduce civilization’s carbon footprint, as there are simply too many humans pouring too many greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Please read my paper which Doug has posted on his website. Global warming is very real, and a issue that we simply must deal with for the good of humanity and planet earth.

Skip Hobbs

Petroleum Geologist

2011-2012 President of the American Geosciences Institute

Skip:

There is no proof. This is pure politics. Climate Gate is the last symptom of Gore and others attempt to try and elevate alternative fuels to the forefront especially since he heavily invested there. I am amazed you actually believe in consensus science. Is it a consensus that the sun is 93 million miles from the earth. Actually Skip, the complexity of this subject is to much for man to even attempt such a solution. The models are trash. It is as bad as trying to solve the origin of life problem. Of course, there are naive people, even educated ones. Human induced global warming is a farce.

Bill Freeman