This post was updated on June 24, 2019.

Now, imagine an opportunity to invest or work in one of two segments of an industry. The first segment, the longtime laggard, has the same chance of outperforming the other—in terms of rewards and opportunity—as does the slower horse of beating the faster. Would you invest your time, money and resources in the laggard? Would you recommend others do so?

Again, for most of us, the answer is no. Only a dupe or wide-eyed romantic would invest in a space that’s expected to so regularly come up short.

But here’s the hard truth: those who bet on the oilfield supplier sector year after year do just this.

Think we’re exaggerating? We’re not.

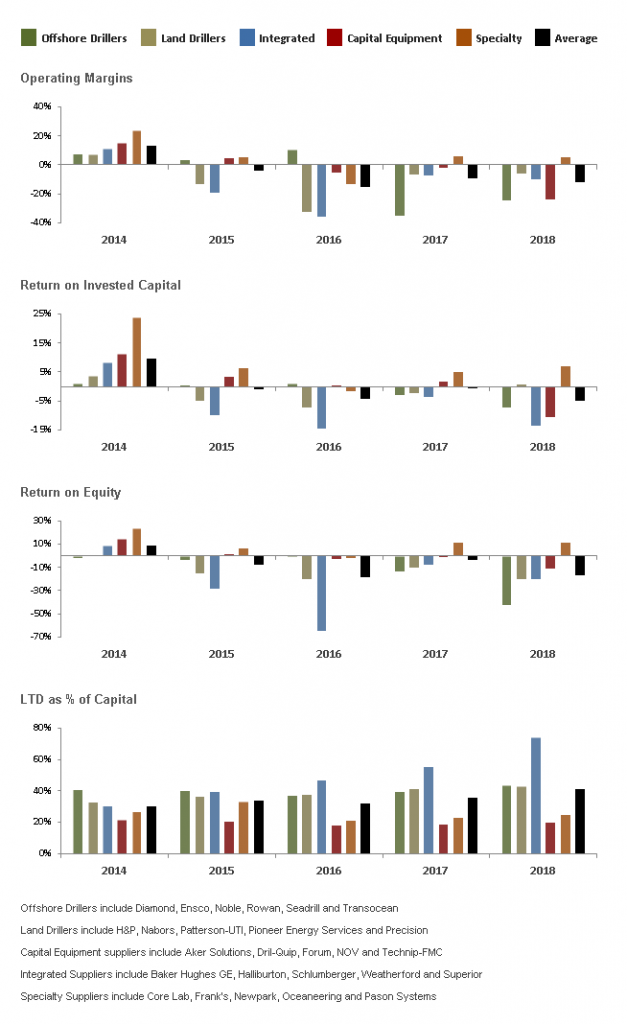

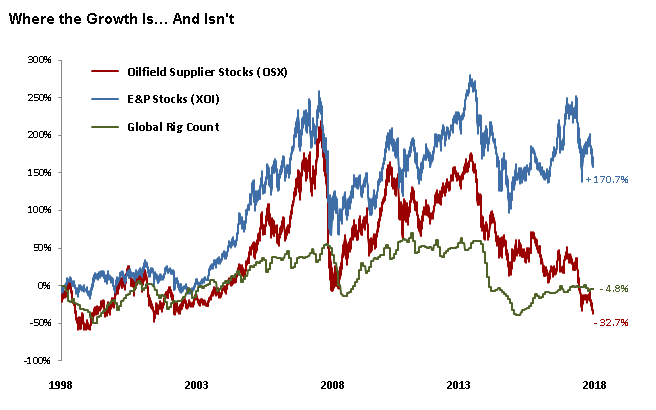

Consider that stocks of oilfield suppliers as measured by the PHLX Oil Services Index (OSX) are at the same level as in 1997—when WTI crude was below $25 a barrel. Today, oil is near $60; yet only a small number of suppliers are profitable.

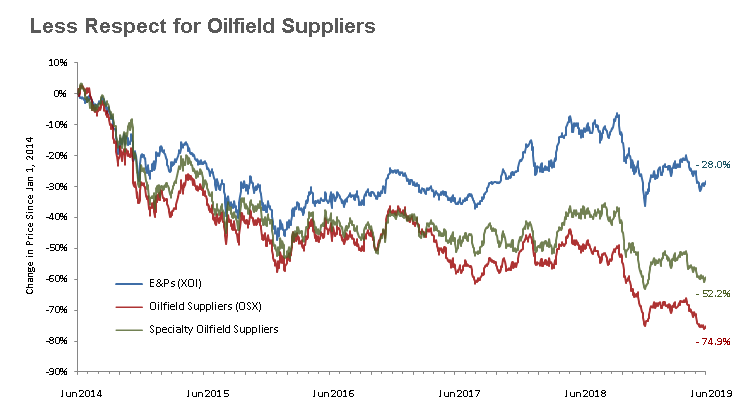

The OSX is down almost 75% since 2014, while the NYSE Arco E&P Index (XOI) is down less than 30%—a huge performance gap.

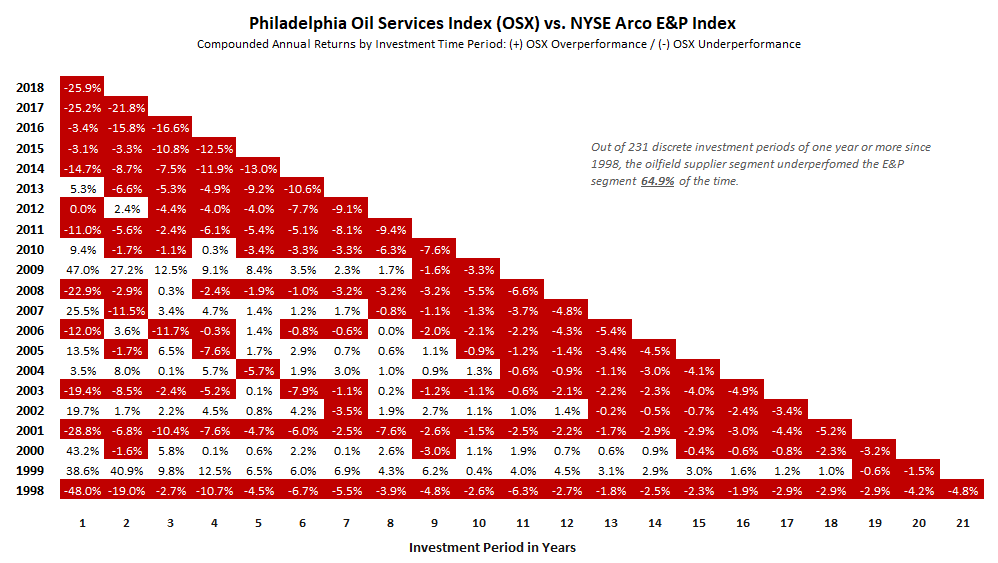

It’s the record of suppliers over decades, however, that’s especially damning.

Executives are often too far removed from customers to grasp the reality. A weakness for both funding and advice from investment banks, private equity and others with short-term interests doesn’t help. In fact, it’s led to an injurious influx of expansion- and survival-capital for a segment that, quite frankly, can’t handle it and doesn’t deserve it.

In the U.S. alone, a total of 167 oilfield service companies filed for bankruptcy from Q1 2015 through Q1 2018, according to the law firm Haynes and Boone. Over half were in Texas, where many of the industry’s most experienced operators reside.

Houston-based Weatherford International could be the poster child for the segment’s unavailing ways. Resting on the belief that customers wanted another global supplier to provide a diverse set of wellsite products and services, Weatherford set out in the mid-1990s to join the ranks of Schlumberger, Halliburton and Baker Hughes.

The company’s growth-through-acquisition strategy was an investment banker’s dream. It fed off the premise that customers would look past inconsistent quality in return for lower prices and packaged offerings. The conceit, which Wall Street analysts happily validated, led others to emulate.

But it turns out the market didn’t need another integrated provider, especially one so sold on price and size over quality and performance. In 2016, Weatherford’s long-time CEO, Bernard Duroc-Danner, was finally forced out, but not before the market laid bare the company’s widespread failings. In May of 2019, Weatherford signaled it would file for bankruptcy, but not before posting 18 consecutive quarterly losses.

This weird ethos hangs like a millstone over the sector—and its reputation. As one ex-executive from a capital equipment manufacturer recently mused: “Why would anyone ever invest in the oilfield supply segment given how often it’s in the tank? Even when times are good, money pours in at rates that depress margins. On average, it’s a terrible business.”

Yes, some will endeavor to reduce costs further by downsizing or combining. Others will attempt to innovate their way out of their predicament—a strategy that will fail for most.

Only a handful of companies will up their games. They’ll embrace quality, execution, stability, and customer focus as central tenets. The long-term winners will emerge from this group. That they can lift the performance—and esteem—of the entire segment remains to be seen.

Top-rated companies in EnergyPoint’s surveys like Valaris, Helmerich & Payne, Core Laboratories, Gardner Denver, Newpark Resources, Derrick Equipment, MarkWest Energy Partners and Plains All-American seem poised to outperform.

These providers, and others like them, are the rare opportunities—for investors and employees. They tend to run their businesses knowing good times don’t last. As competitors fall away, they take up the slack bit by bit, steadily growing market share and earnings—usually organically. All the while, they build expertise, invest in their brands, and guard their reputation.

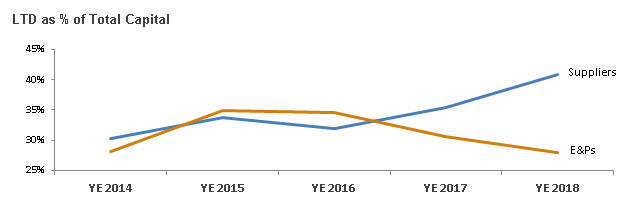

Stocks of oilfield suppliers are down more than 30% over the last 20 years, even as E&P stocks have appreciated 170%. How is this disparity so easily ignored by executives, markets, employees, and others? No industry can thrive when its supplier base languishes like this.

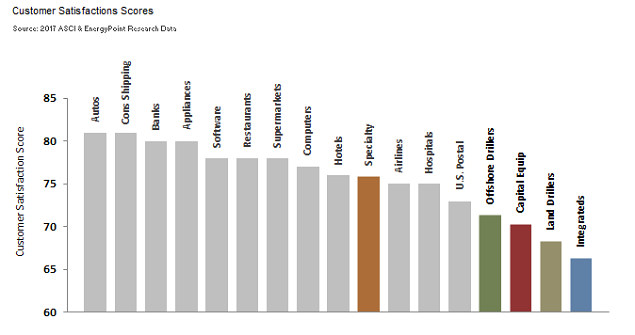

It’s not clear why industry suppliers don’t get that higher quality and customer satisfaction lead to stronger financial performance. But clearly, most don’t. And it’s a big problem.

It’s been said that hope is not a strategy. Yet, hope—that suppliers will finally and magically get the credit they deserve, that commodity prices will cooperate, that marginal competitors will soon capitulate—has fueled the space for decades. Isn’t it time we acknowledge this illusory mindset isn’t working?