Few sectors have ever fallen farther over an extended period than oilfield suppliers have since the current industry downturn began in June 2014. Relative to the broader market, the sector’s decline may be unprecedented.

Six years ago, Saudi Arabia fatefully declared it would no longer hold millions barrels of production off the market in support of global oil prices in excess of $110 per barrel.

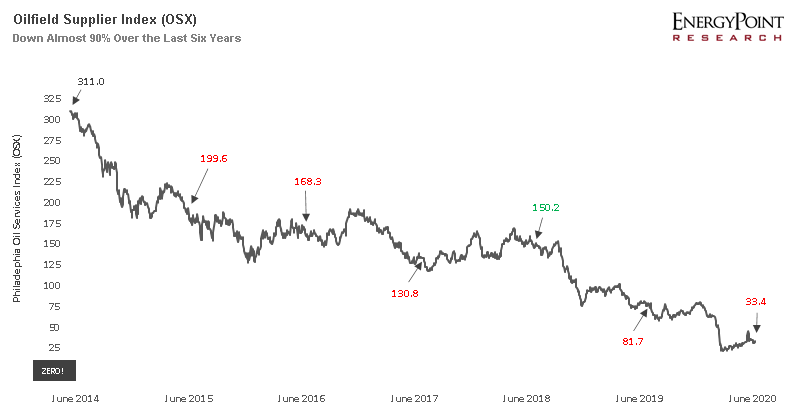

The market responded swiftly, and crude was near $60 within a year. The supplier sector, as measured by the Philadelphia Oil Service Index (OSX), fell by 35%. The tailspin was on.

In each of the next two years, the OSX fell 15.7% and 22.3%, respectively. The following year, fueled by unfounded faith in the U.S. shale-oil story and a strengthening forward curve, the index managed a 14.8% gain.

But as suppliers moved to cut-throat pricing in response to overcapacity, the index fell by 45.6% the following year. That wasn’t the worst of it. With oil demand waylaid by the Coronavirus pandemic, the index is down by an almost-impossible 59.2% for the most-recent 12 months ending June 30 of this year.

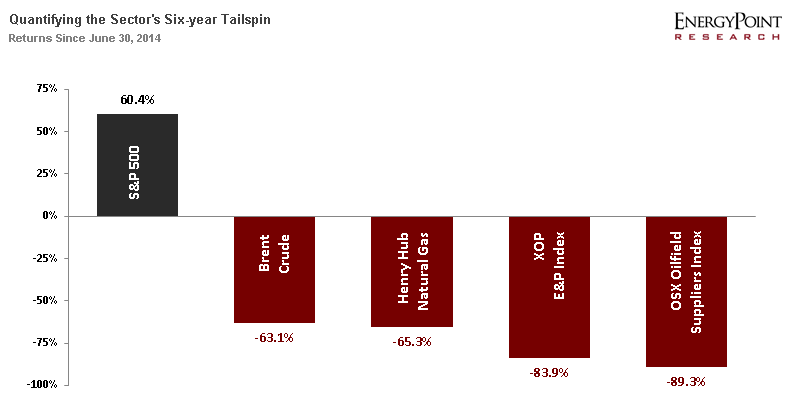

All tallied, over this six-year period the OSX is down 89.3%—even as the broader S&P 500 Index is up by 60.4%. The OSX, launched in 1996 at a base value of 75, hit its all-time low of 21 on March 18. At one point in the rout, an OSX in single-digits was not out of the question.

Brent crude is down 63% and Henry Hub natural gas is off 65% over the same period. The S&P E&P Index (XOP) is down 83.9%.

While there’s been plenty of bad luck to go around, fortune can’t explain the intractable refusal of many in the supplier community to do much other than wait with crossed fingers. The main culprit is an almost mystical belief that somehow, someway cash-strapped customers—after deftly exploiting suppliers’ commitment and sacrifice—will eventually start paying premiums for the very same products and services they’ve worked so hard to commoditize.

One problem is lack of awareness. Too many executives at suppliers seem to believe the huge footprints their companies developed during the 2003 – 14 “oil-scarcity” boom will be required going forward. Nothing could be farther from the truth.

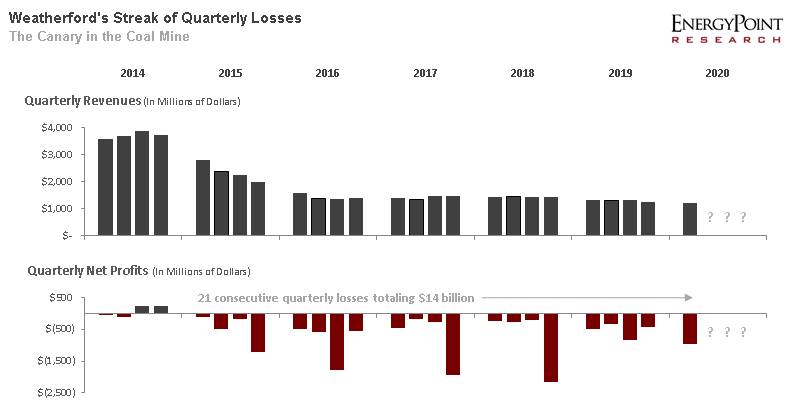

This shouldn’t come as a surprise. In fact, EnergyPoint began sounding the alarm in 2017. Even prior to this, the sector had its own “canary in the coal mine” pointing to the unsustainability of many suppliers’ business models.

In 2014, Weatherford International was the fourth largest oilfield supplier on the planet behind Schlumberger, Halliburton and Baker Hughes. The company spent untold billions building a full-service global provider designed to ride the oil and gas industry into the twenty-first century. In reality, with me-too strategies and too many lackluster offerings, the company was never really more than an also-ran.

When the industry downturn took hold in 2014, the veil fell. Beginning in 2015, Weatherford began a streak of 21 consecutive quarters of net losses totaling more than $14 billion. The coming quarter will likely be the 22nd.

When the fourth-largest supplier to an industry that spends half-a-trillion dollars per year fails—in very public fashion—to earn a profit for five years running, the entire sector needs to take a hard look at the road forward.

Those that do will find that unless suppliers—even those that emerge from bankruptcy with clean balance sheets—start to truly differentiate themselves from peers, their prospects remain dim. Yes, maybe a price spike here or there will materialize. But suppliers need greater power and ambition in their strategies if they are to survive over the long term.

The byword in the sector must be focus; the tools fact-based decision-making and unemotional mindsets.

While it can be risky to toss aside old ways of doing things without adequate analysis, crises have a way of diminishing resistance to change. Jettisoning legacy businesses becomes more palpable, and outdated norms more easily challenged. Sacred strategies fall away.

The companies that make the necessary changes and ultimately survive will see opportunity. The global petroleum industry may be on its heels, but it remains immense. Despite the move toward decarbonization, the world will need oil and gas for decades. Even during the peak of the pandemic, demand for oil dropped by only 20%.

Supermajors like ExxonMobil, BP, and Shell have huge existing reserves that will take decades to produce. State-owned giants like Saudi Aramco and Petrobras have even more. They will all spend to add to reserves. In North America, the industry will be smaller but far from vanquished.

In the end, the smartest players will capitalize on existing skills, assets and market positions by sticking to what they do best… and then figuring out how to do it even better. Those that structure themselves to be profitable when oil is below $50—through smart downsizing and consolidation, leaner operations, stronger balance sheets, greater focus on customer satisfaction, and even selectively moving into other energy-related fields—have the best chance of surviving. Eventually, some will even prosper.